THE VIDEO BOOK OF ORCHIDS (2021)

The making of the film The Video Book of Orchids was sponsored by Empire & Ecologies, UCD, Dublin.

This film steals its title partly from an Australian documentary I have never seen called The Video Picture Book of Roses, which focused on close-ups of blooms in a Hall of Fame of traditional rose gardens. As soon as I heard this title, I became fascinated with the format of the book video, and how it might relate to the seriality of flowers, as well as the order and disorder of reading.

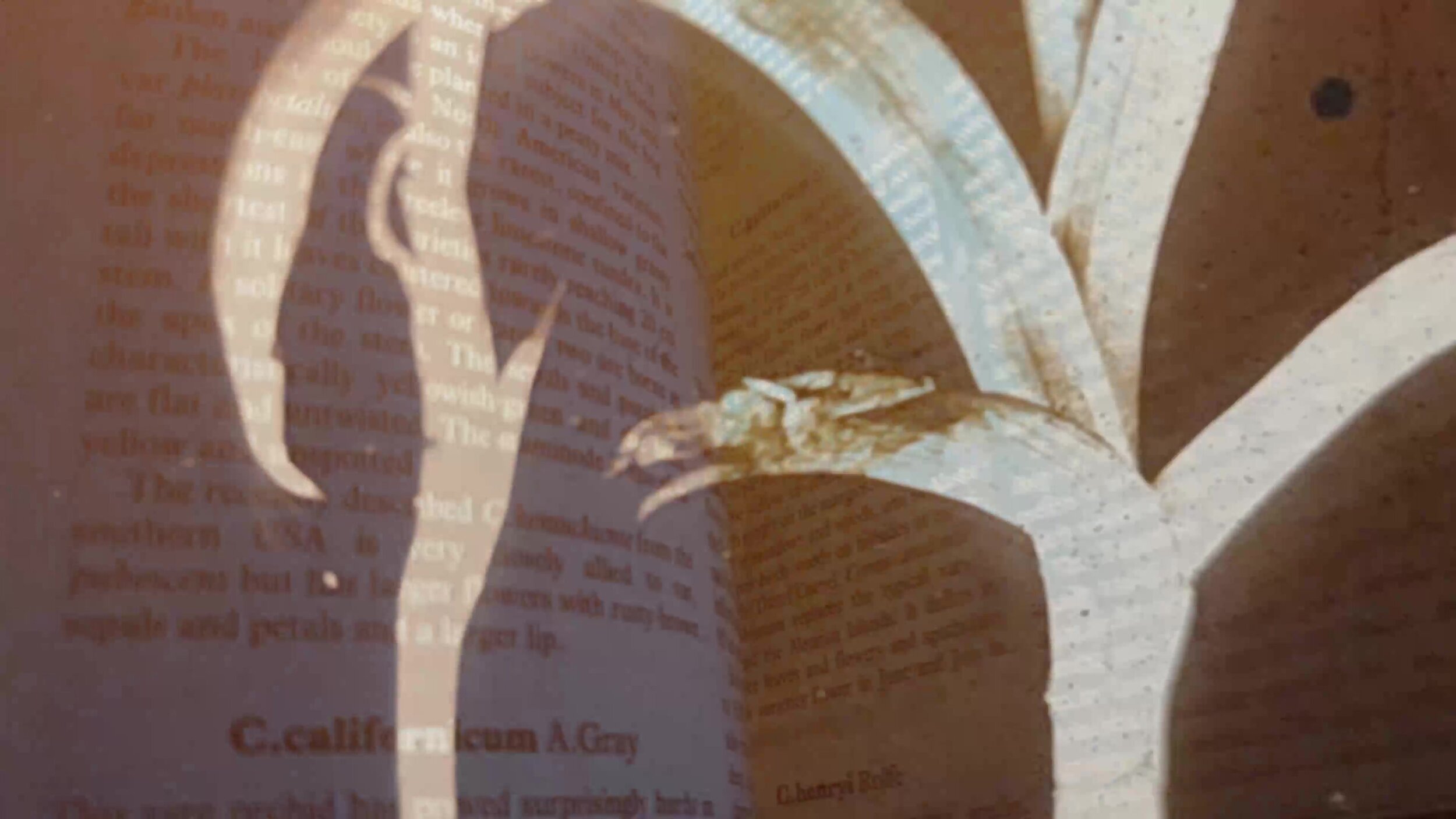

Since this was made for the creative praxis panel of UCD’s Empire & Ecologies international symposium, I focused on technique as much as research. The sound design of the film, for instance, included making musical compositions and field recordings of butterflies and greenhouse air circulation, as well as sampling Librivox public domain recordings of historical orchid literature by international readers, and snippets from my own experiences through online conversations, broadcasts, and events. I was interested in the public domain in particular, and the public lives of these flowers as international “ambassador plants” – including my interpretation of the digitised scrolling of the Reichenbachia, originally published as extravagant leatherbound “imperial folio” editions of chromolithography prints on fine biscuit paper (since nicknamed the “Rolls Royce” of orchid books).

I saw this work as a kind of geography, in the sense that geo-graphy means the mediation of the earth, and a shift from James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth (1788) to media of the earth, i.e. the passage of different ways of mobilising the earth into and as media. I am inspired by the work of media archaeologists such as Jussi Parikka and Sean Cubitt, who both describe the articulation of the human precisely through our positioning of ourselves relative to the ecology of mediation: as Parikka writes, ‘The human being is primarily a “so-called Man” formed as an after effect of media technologies’.

A problem with approaching filmmaking as a researcher is that you cannot include all of the information in words. This film was prompted by a research group which asks, trans-historically, how are environments shaped by empires, and how are empires shaped by environments - from the imperialism of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, to forms of new imperialism in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? This also includes the environment of the book, as well as digital re-mediation, which I think is part of the question that a moving image work essentially always poses. Through the audio-visual processes I was developing, I tried to suggest at themes I couldn’t represent at length in words, such as Darwin’s many letters on the postage of orchid specimen samples, and the suggestive language of his “transport of admiration” when encountering a specimen.

It was also interesting to discover that Darwin’s big book on species theory revolving around the variation and fertilisation of orchids (1862) was itself originally published as a smaller series of variations, or “interruptions”. He noted in his journal on 9 January 1860, ‘Began looking over M.S. for Work on Variation (with many interruptions)’. I loved this piecemeal idea, and the fact that reading strategies for plant lives might be interrupted and interrupting. This seemed to my mind to fit his wider arguments about inter-crossing, adaptation, and the many ways that species mediate each other – as well as drawing on my existing audio-visual interests in the monsters that haunt taxonomy, and the ideology of “glitch” and “hacking” traditional models for nature. Some of this may not be obviously noticeable: for instance, the sequence of flipping through the pages of the various printed Orchidaria is scored not just with my recordings of their own pages riffling, but also my field recordings of butterfly wings and butterfly houses. The sounds combine to, I hope, open both dimensions at once, while still remaining somewhat hidden. I didn’t want a more explicit representation of butterflies in the film, since they are renowned as the invisible partner in their complex co-evolution with the orchid – a kind of ghostly relationality and work of suggestion. But I did want to mark these invisible partnerships, which mean that one key consequence of our treatment of the botanical family during the Anthropocene is the overlooked extinction of masses of insects, which has been referred to as a global “death by a thousand cuts”.

This film was made in lockdown in 2021 during the season when Kew Gardens would usually be hosting their orchid festival and display. I wished to explore, rather than shut down, both narrative strands – of the violence, as well as the hope, of the herbarium model.

See further context in the online essays Behind the Beauty of Orchids, Centuries of Violence and The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Orchids.